Senior kindergarten program

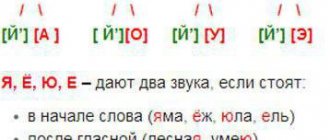

The main task of literacy classes in the senior group of kindergarten is to teach the action of sound analysis of words. During this training, children become familiar with vowel and consonant sounds, learn that consonant sounds are hard and soft, and learn the letters that represent vowel sounds. The teacher begins classes in the older group by introducing the children to the scheme of sound analysis of words. For these lessons we used the contents of Part I of D. B. Elkonin’s “Primer” on cards. Thus, in front of each child in class there is a card on which an object is drawn, a word - the name of which will be the subject of analysis, and under the picture - a diagram of the sound composition of the word; the same picture on an enlarged scale hangs on the board. In addition, each child has a tray with chips in front of them. The chips can be made of any material - identical pieces of cardboard, identical plastic plates of some neutral color - white, gray. We recommend an individual tray for each child, since the number of chips for work will gradually increase, reaching a dozen by the end of the lesson, and such a quantity of different material, folded together for two children, is inconvenient for use. Each child should also have a small pointer - it is convenient to use counting sticks for this. It is clear that you cannot place a counter on a table hanging on the board, so the material for working at the board has a slightly different look. The table is made from a standard sheet of Whatman paper, its lower edge is folded and secured with a strap. Chips are placed in the pocket thus formed - rectangular pieces of cardboard with narrowed lower ends. Having introduced the children to the diagram of the sound composition of a word, the teacher moves on to forming the action of sound analysis of words. If the group has mastered the previous year's program material well, the children easily understand the teacher. In the same case, if the teacher discovers that most children do not cope well with the intonation of sounds in a word, it is necessary to immediately stop classes on forming the action of sound analysis of a word and return to the middle group program. A few lessons will be enough to review past material and move on to new tasks. Based on the children’s previously developed ability to distinguish sounds in a word intonationally, the teacher must teach the children to pronounce the word being analyzed, while simultaneously moving the pointer along the diagram of the sound composition of the word. It is important to achieve complete synchrony in pronunciation and movement, to make sure that this synchronicity is not accidental, that children can slow down or speed up the movement of the pointer depending on which sound in the word is intonationally emphasized. Only after making sure that children are oriented in the scheme of sound composition can we proceed to identifying individual sounds in a word. We have already shown that intonation highlighting is a simpler way of modeling the sound composition of a word than a sound composition diagram and chips. Therefore, it is important to move on to complex forms of modeling only after mastering the more elementary forms of natural modeling. A prepared group of children easily learns the method of sound analysis of words using intonation, a diagram of the sound composition of a word and chips. However, not all children immediately begin to work equally successfully. The method of conducting sound analysis of a word that we will teach children throughout the year is the same for analyzing any word, therefore, giving more and more new words for analysis (and this is absolutely necessary to eliminate the moment of mechanical memorization of sounds in a word), the teacher gradually ensures that all children in the group master the program material. First, children are offered three-sound words for analysis: poppy, house, cheese, whale, cat, ball, onion, beetle, smoke, nose, cancer. At each lesson, children first learn one new word. However, this word is analyzed several times in different ways. First, children are asked to simply parse a new word, for example, house. The whole group works at the tables, and one child at a time is called to the board to highlight each sound in a word. The word is pronounced with intonation highlighting the desired sound, the pointer fixes this sound on the diagram, then the corresponding cell of the diagram is filled with a chip. The next stage is when the teacher suggests removing chips from the diagram in accordance with the sounds he calls. In this case, the sounds should not be named in the order in which they appear in the word, it is better to name them separately: “Remove the sound o, now the sound m, what sound remains?” This kind of task forces children to carefully conduct a sound analysis again, to examine the sound composition of a word according to the scheme. It is very good to consolidate sound analysis in the form of a game: three children are called to the board, each of them receives a chip and the name of the sound (“You will sound d”). Then the teacher calls the “sounds” to himself: “Come to me, the sound d, now come the sound m, come the sound o.” Children should stand in the same order as the sounds in the word. Gradually, the game becomes more complicated: the teacher distributes sounds to the children by numbers (“You are the first sound in the word, you are the second,” etc.), and calls them to him by the names of the sounds (“Come up, sound m”). In order to complete such a task, the child, who has received the number of the sound in the word from the teacher, must read the word according to the scheme with intonation highlighting and thus find out what sound it is in the word. Different versions of this type of game make it possible to interview a large number of children during the lesson and offer them tasks that correspond to their capabilities. The teacher includes in classes many tasks that develop in children the most important mental operations of comparison, comparison, and analysis: find the same sounds in the words house and poppy; find different sounds in the words house and smoke; what words we analyzed that end with the same sound with which the word cat begins, etc. The tasks can be very diverse, but when giving them, the teacher must take into account the individual capabilities of each child. It is very important to ensure that all children in the group actively work in class. But this is only possible if the teacher sees and knows every child. The most active and well-prepared children can quickly get bored with monotonous and easy tasks, so the teacher should give them more complex problems to solve (for example, searching for different sounds in words is more difficult than identical ones). You can also give a task that cannot be completed: find the same sounds in the words house and cancer. Passive children, on the contrary, can be scared away by tasks that are beyond their strength and instill in them even greater self-doubt. We recommend warning such children in advance that they will be called to answer (“Now Kostya will finish parsing the word, and then Marina will remind us what the second sound is in this word”), this will give the child the opportunity to gather himself internally and prepare to go to the board. After all the three-sound words we offer have been analyzed and the children have mastered the method of conducting sound analysis, a new point can be introduced into teaching - the distinction between vowels and consonants. We attach great importance to the fact that as many “discoveries” as possible are made by the children themselves. Therefore, we propose to introduce vowels and consonants in the following way. The teacher hangs on the board a table familiar to the children, on which a poppy is drawn, and asks them to guess the riddle: “This word has one sound - extraordinary. This sound can be shouted very loudly, we can sing it, when we pronounce it, nothing in our mouth interferes with us - neither lips, nor teeth, nor tongue. Guess what that sound is?” Children guess that this is the sound a. They also choose from the words the sounds o (house), u (beetle), y (smoke), and (whale). Only after this the teacher combines all these sounds into one group and says that they are called vowels, in contrast to consonants, which cannot be shouted, sung, or said without anything getting in the way in the mouth. Children are asked to name consonant sounds from the words shown on the tables. Sometimes children make mistakes, naming the vowel sounds r, l, etc. Each time you need to analyze such a mistake in detail, try to shout this sound out loud together with the children, and see if anything is stopping you from pronouncing it. Such a definition of vowels and consonants, not learned, but as if made independently, is firmly assimilated by children; they easily operate with their knowledge. From this lesson, children begin to denote all vowel sounds with red chips, and all consonants with blue chips, the white chips are removed, and the children no longer use them. Of course, in the future, when parsing four- and five-sound words, children will make mistakes more than once, confuse vowels and consonants, but they will easily correct their mistakes by remembering how they themselves divided all the sounds into vowels and consonants. You should move on to the analysis of four-sound words immediately after becoming familiar with vowel and consonant sounds. We propose to parse the following words: saw, moon, fish, fox, sleigh, soap, geese, beads. All these words are very easy for sound analysis, children can successfully parse them. Complications in classes come from sound games. The familiar play with the sounds of the word we have just learned has changed noticeably thanks to the emergence of a new distinction between vowels and consonants. Now the teacher, having “distributed” the sounds of the word to the children by number, can call them to him as vowels and consonants (“Come to me, the first vowel sound in the word, now the second consonant,” etc.), and put ( put the chip back on the diagram), calling them sounds (Insert the sound a, replace the sound n, etc.). It is clear that in this form this game requires good mastery of the action of sound analysis of words, free orientation in the sound composition of words, and a solid knowledge of all the material covered. The child cannot complete the teacher’s tasks based only on memorization; he must constantly think actively. The second game, which was started in the middle group of the kindergarten, consists of naming words that meet some condition set by the teacher. If at first the tasks were simple, such as “Name a word that has the sound p,” then gradually they become more difficult: “Name words that begin with the third sound of the word rose.” This is a competition game, for each correctly named word, children receive a chip, and at the end of the game, when counting the chips, the winner is determined. In addition, during this period, the teacher introduces children to a new game: naming words based on the model of the sound composition of the word. For example, chips are placed on the board: blue, red, blue; children are asked to name words that have such a sound composition. At first, the words are named uncertainly, mainly those that were analyzed in the group, but gradually the children get used to this new type of work and begin to name many different words. Let us give as an example the words named by children according to the scheme proposed above in the middle of the year: poppy, whale, hall, gas, current, onion, cat, oak, ball, beetle, house, steam, forest, heat, cheese, smoke, varnish, floor, knife, spirit, sleep, bass, ball, pillbox, bow (the child clarifies: “Not the one that they eat, but the one they shoot from”), bot, horn, step, fluff, rad, noise, nose, forehead, mouth , ox, elk, crowbar, Chuk, Huck, forelock, steam, beat, hall, moth, shield, din, there, basin, oven, himself, chalk, son, daughter, catfish, rubbish, Muk, May, rye, etc. Games of this type, with the model gradually becoming more complex as new words are learned, continue throughout the year. The next stage of learning is familiarization with soft and hard consonants. We considered it necessary to introduce these new concepts in the same way as we introduced vowels and consonants at the previous stage, that is, to give the children the opportunity to discover the difference between the consonants themselves. To do this, the words saw and fox are discussed in class. After the children have carried out a sound analysis of these words, the teacher invites them to remove the same vowel sounds. Children remove all red chips from the diagrams. Then the teacher asks to remove different consonant sounds from the diagrams - the children remove the chips indicating the sounds p and s. “What sounds do we have left?” - asks the teacher. "Sound L." - “Are these sounds the same or different?” - “Identical” - “Let’s listen carefully to how the sound l sounds in the word saw and how it sounds in the word fox: saw, fox. Does it sound the same? In each group there are always several children who answer that the sound l in these words does not sound the same: in the word saw - rudely, and in the word fox - affectionately. The teacher supports these children, but changes their wording: “The sound l sounds hard in the word saw, but softly in the word fox.” Then the teacher invites the children to determine in the pairs of words he calls where the same sound sounds hard and where it sounds soft. All children are good at distinguishing hard and soft consonants by ear, although this, of course, does not mean that in the future, when analyzing new words and filling out the diagrams of the sound composition of words with chips (now children denote soft consonant sounds with green chips, and hard ones - still with blue ), children don't make mistakes. They often forget about new definitions, but the teacher’s request: “Listen carefully to how this sound sounds: soft or hard?” - invariably leads to the correction of the error. Having learned to distinguish between vowels, hard and soft consonants, children move on to parsing increasingly complex words with a combination of vowels and consonants: duck, spider, leaf, stork, bush, needle, elephant, wolf, doll, cherries, bag, bear, desk, mouse, tiger, watermelon, sugar, etc. In all these classes, we continue to practice in children the action of sound analysis of words, gradually achieving free orientation in the word being analyzed from all children in the group. It is clear that with the introduction of the distinction between soft and hard consonants, all types of games described above have become very complicated: in the game “Sounds of Words,” the teacher has the opportunity to give many options for tasks to children, and, what is important, tasks that are very different in complexity. The number of words examined in class gradually increases: children learn 3-4 new words. It is very important to draw children’s attention to different patterns of the sound composition of a word and compare words according to patterns. When asked by the teacher what previously analyzed word the word wolf is similar to, the children confidently answer: “To a bush, there is also first a hard consonant, then a vowel, and then two more consonants.” This promotes the development of a game of naming words using new, complex patterns. By this time, when analyzing words, children stop using the diagram of the sound composition of the word and lay out the chips in front of them directly on the tables. We lead children to abandon the scheme very gradually. First, we offer children a new word for analysis, without hanging the corresponding table in front of them, the diagram on which tells the children the number of sounds in the word. The teacher slowly (but in no case syllable by syllable!) pronounces the word and asks the children: “How many cells do you need to make out this word?” Very quickly, children begin to determine the number of sounds in a word (from 3 to 5) by ear and choose a diagram with the appropriate number of cells to work with (children no longer receive pictures, each child has a set of diagrams of 3, 4, 5 cells). Soon these diagrams also become unnecessary, the children lay out chips on the tables, constantly testing themselves, “reading” the analyzed word with a pointer in the same way as we taught them at the beginning. It should be noted that such “reading” with a pointer and with intonation is preserved for a very long time in children. Even after moving on to “reading” without emphasizing any sounds, children, in case of difficulties, immediately begin to intonationally highlight the desired sound again. It would be wrong to think that this kind of pronunciation is evidence of insufficient formation of the action of sound analysis of words and that this must be fought. It must be assumed that for children of this age, a complete refusal to model the sound composition of a word in the external plane is generally impossible: even the most prepared children, parsing “in their minds” easy words (with open syllables), return to pronouncing and acting with a pointer when moving on to parsing words with complex consonant clusters. We tried to take the pointer away from the children, they began to use their finger as a pointer and continued to whisper the word. Finally, the last stage of work in the senior group of kindergarten is familiarization with vowel letters. Each new letter is entered in the same way. Let's show this using the example of the letter a. Children are asked to make out several words: brand, lamp, tap. Models of these words are laid out in front of the children on the table and on the board. Then the teacher asks the children to find the same vowel sounds in the analyzed words. Children determine that this is the sound a. Then the teacher shows the letter a and, having examined it with the children, asks to replace the corresponding sound in all words - the red chip - with the letter a. Then the children parse the words, always putting the letter a instead of the sound. At each lesson, children were given a new letter to familiarize themselves with. We introduced the children to vowel letters in pairs: a - i, o - e, u - yu, etc. How was this done? In the next lesson, after learning the letter a, the children were offered the words melon, rag, and meat for analysis. Parsing the word melon, the children laid it out like this: a hard consonant (blue chip), a vowel sound (red chip), a soft consonant (green chip), sound a (letter A). The teacher shot the letter A from the scheme and told the children: “Remember one very important rule: after a soft consonant, the letter is never written, I write instead of it. As soon as the letter A sees a soft consonant in front of her, she runs away without looking back, and the letter “I” runs instead. It should be noted that children do not immediately absorb this rule, we observed cases when our individual pupils forgot for several classes where and when which of the letters is written. But we repeated a new complex rule when analyzing each word, asking the children: “Why did you put the letter here? I hear the sound a "." Gradually, the weight of the group’s children clearly answered: “After a soft consonant, the sound is indicated by the letter I. The letter is impossible to write here. ” In the same way, all the other vowels were introduced in pairs. For better assimilation of the rule, we introduced a special game “Find your place”. The game is as follows: each child’s child receives some vowel letter, two children hold green and blue chips in their hands, meaning a soft and hard consonant sound respectively. At the signal of the educator, all letters should stand up to their sound: letters A, o, y, y, e - behind a blue chip, letters I, ё, yu, and, e - for green. The game helps children to fix the already learned rule, it goes a lot of fun. At this stage of training, we slightly modified the game consisting in naming words according to the model. The teacher puts on the board a model of a word and invites the children to guess what word he has planned. It is already not enough just to call any word with a similar sound composition, you must definitely guess the word conceived by the teacher. Why did we introduce this kind of change? When guessing riddles, children should learn to raise questions to the educators, clarifying the field of reality to which this word belongs. Let us give an example of such a game. The teacher puts the following model on the board: green chip, red chip, blue chip, red chip. Children begin to call the words: Misha, Nina, Summer, Winter, Mina, saw. E. So you will not guess for a long time, because you need to first find out what I made a riddle about. I. Is this a person or object? E. Not a person and not an object. I. Is this a bird? E. no. I. Is this an animal? E. Yes. I. And what kind of animal: wild or homemade? E. Wild. I. is it forest? E. Yes. I. Fox. The riddle is guessed. It is clear that the given example of guessing is a kind of sample. Children do not immediately master the method of deductive issues, they need to be specially taught. At the next stage of the development of this game, children themselves make riddles, laying out a model of conceived words on the board. In this case, the teacher is also included in the guessing of the riddles. It should be noted that children make riddles incomparably more complex than a teacher consisting of a large number of sounds. The game of riddles becomes one of the favorite children's games, they often play it. In general, by the middle of the year, children, in addition to classes, often play various speech games on their own. The introduction of materials like those with which children work in the classroom in a letter contribute to the fact that children begin to play “to school”, setting each other words for sound analysis. The most prepared children teach those who are in the classroom. Children finish the program of the older group, having the following knowledge and skills: 1. They know how to conduct a sound analysis of almost any proposed word. 2. Distinguish vowels, solid and soft consonants. 3. They are freely oriented in the sound structure of the word, select words according to the proposed models. 4. They know all vowels and can explain the rules for writing vowels after soft consonants. Classes should be held twice a week. At the beginning of the year, the lesson is designed for 20 minutes, at the end of the year it increases to 30 minutes.